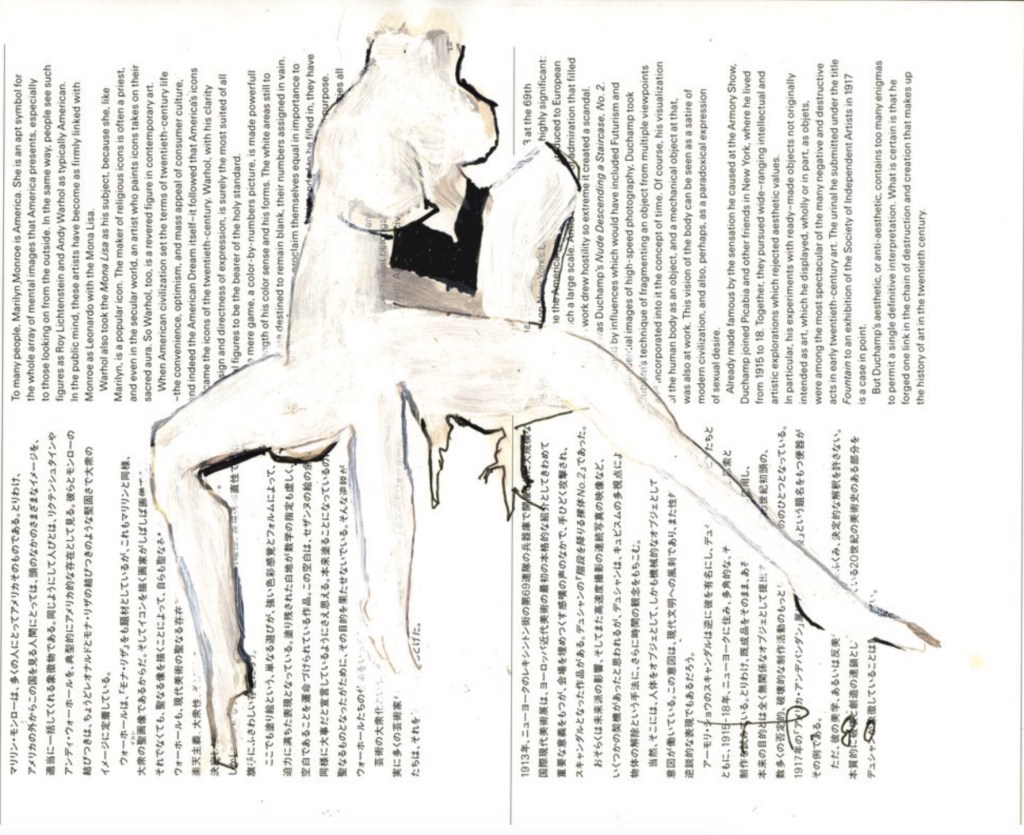

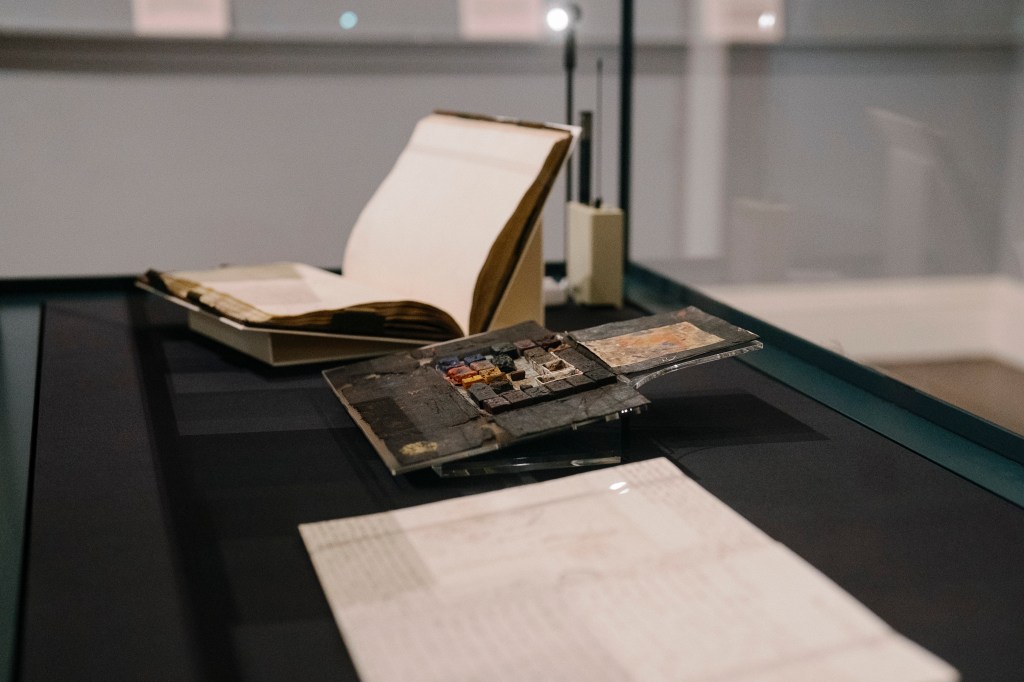

Sometimes it is not the main feature of an exhibition that really draws you in and captures your imagination, but instead, a smaller component that others attending the show may not even have noticed. At the exhibition Austen and Turner: A Country House Encounter I was drawn in by J.M.W. Turner’s paint palette: a rudimentary object that the artist had fashioned himself from pieces of card, still with the paints in little ceramic dishes within it. It was so charmingly quaint and intimate to see up close: in the exhibition, it was closely followed by Jane Austen’s first editions – books within glass cases, mostly in pristine condition. Still, the palette afforded a sense of intimacy that the books did not, most likely because it was handled and indeed made by Turner himself, while the books had been through the publication process.

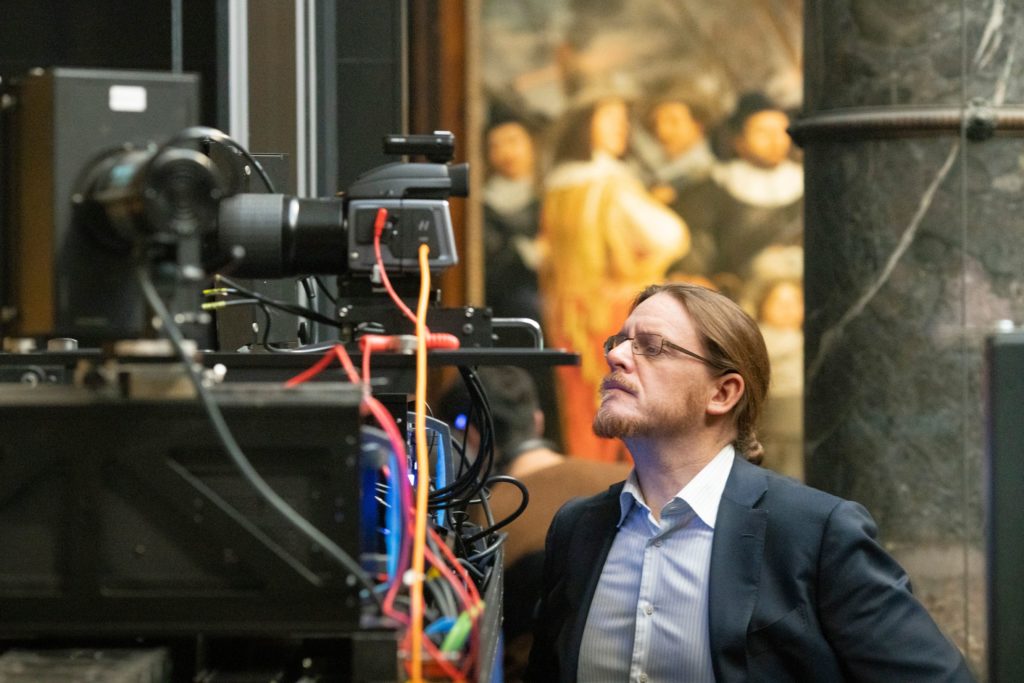

JMW Turner, Photo credit: ©Royal Academy of Arts, London

The drive up to Harewood House in Yorkshire is a lengthy one, filled with beautiful English countryside to rival any royal park both in beauty and in scale. This year, the house hosts a landmark exhibition, Austen and Turner: A Country House Encounter, celebrating the 250th anniversaries of two titans of British culture: the landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) and the novelist Jane Austen (1775–1817). This groundbreaking exhibition, co-curated by the Harewood House Trust and the University of York Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, imagines a meeting between these well-loved figures, looking at their shared interest in the British country house and its cultural significance during the Regency era. While there is no historical evidence that confirms that Austen and Turner actually met in person during their lifetimes, their connections to Harewood House and their parallel insights into the social and aesthetic worlds of their time offer a vivid and compelling narrative.

J.M.W. Turner and Harewood House: A Formative Commission

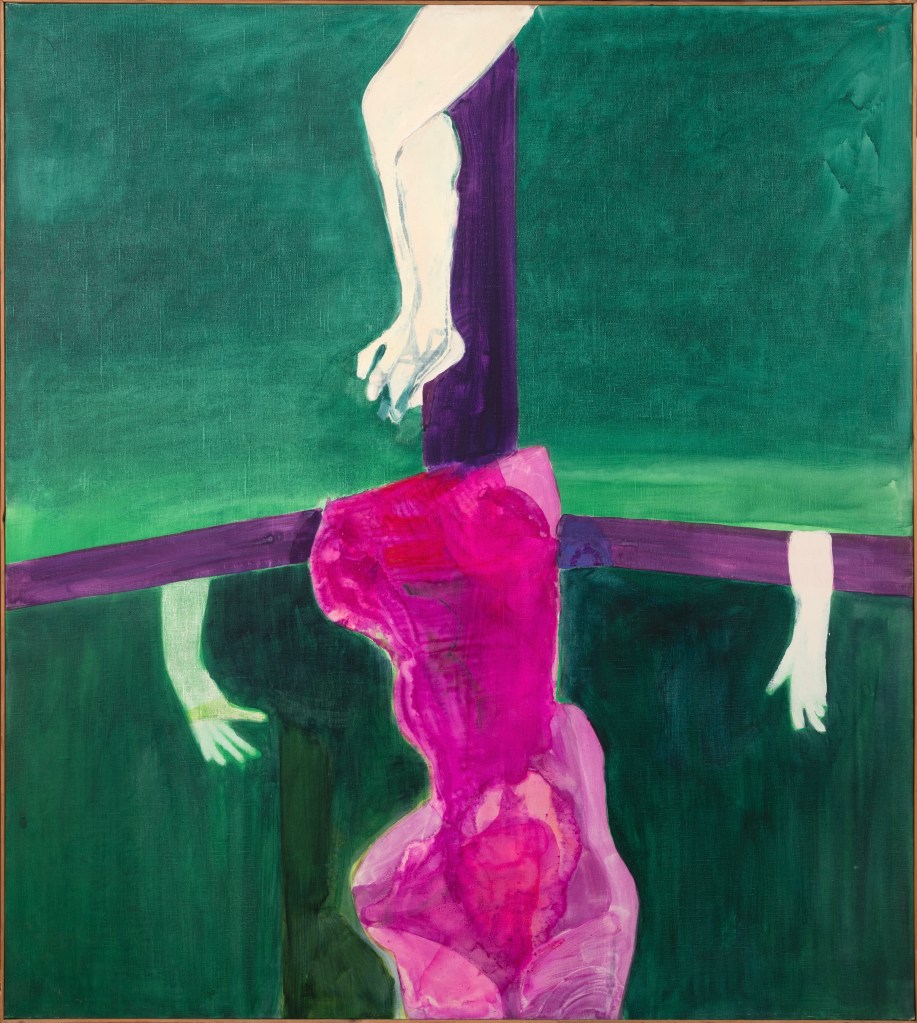

J.M.W. Turner, often hailed as the “painter of light,” was a transformative figure in British art, elevating landscape painting to rival the long prestige of history painting. His connection to Harewood House began in 1797, when, as a young artist of 22, he was commissioned by Edward Lascelles, Viscount Lascelles (1764–1814), to create a series of watercolours depicting the estate: some of these are on display for viewers within the exhibition. This commission marked a pivotal moment in Turner’s career, transitioning him from an architectural draftsman to a serious landscape painter.

Harewood House, a Palladian masterpiece built in 1759 by Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, was an ideal subject for Turner’s budding talent. Designed by Robert Adam and set within a landscape crafted by Capability Brown, the estate embodied the grandeur and cultural aspirations of the British aristocracy, with its extensive gardens and neo-classical facade. Turner’s visit in the summer of 1797 was part of an extensive tour of northern England, during which he filled two large sketchbooks with nearly 200 drawings, capturing landmarks like Kirkstall Abbey and Durham Cathedral. At Harewood, he focused on the house and its medieval castle ruins, producing six large watercolors—four of the house and two of the castle—for which he was paid 10 guineas each.

These works, including Harewood House from the North-East and Harewood Castle from the South East, showcase Turner’s early mastery of light and atmosphere. His depiction of the castle ruins, with their ivy-clad towers set against the expansive Wharfe Valley, reveals a romantic sensibility that would define his later work. The exhibition at Harewood reunites these watercolors, some of which had been separated since 1858, alongside rarely seen sketches from the Tate’s Turner Bequest and the aforementioned paintbox he used during his visit. These artefacts highlight Turner’s meticulous process and his ability to capture the emotive power of the landscape.

Turner’s connection to Harewood was not merely fleeting. Edward Lascelles, a patron with keen artistic sensibilities, supported young, avant-garde artists like Turner and his contemporary Thomas Girtin, who also painted Harewood. The 2015 exhibition Mr Turner and Mr Girtin: The Early Years at Harewood compared their approaches, noting Turner’s luminous precision against Girtin’s softer, more atmospheric style. This patronage underscores Harewood’s role as a hub for artistic innovation, a tradition that continues with contemporary responses to Turner’s work in the 2025 exhibition.

Jane Austen and Harewood House: A Literary Connection

Jane Austen, born the same year as Turner, was a novelist whose sharp social observations and nuanced portrayals of the British gentry remain unparalleled. While Austen never visited Harewood House, her work and life intersect with its cultural and historical context in intriguing ways. The exhibition posits Harewood as a real-world parallel to the fictional estates in Austen’s novels, such as Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice, which symbolize wealth, status, and moral character. Harewood’s opulent interiors, extensive grounds, and colonial wealth—derived from the West Indies sugar trade—mirror the settings Austen critiqued and celebrated.

Austen’s awareness of Harewood is suggested through her reference to the Lascelles family in Mansfield Park. A minor character, Mrs. Lascelles, evokes the family’s name, hinting at Austen’s familiarity with their prominence. The Lascelles’ wealth, tied to slavery and empire, resonates with the themes of colonialism and moral ambiguity in Mansfield Park, where Sir Thomas Bertram’s Antiguan plantations underpin the family’s fortune. The exhibition includes a first edition of Sense and Sensibility from Harewood’s collection, alongside the original manuscript of Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, displayed in northern England for the first time. Sanditon is particularly significant for featuring Miss Lambe, Austen’s only character of African descent, reflecting her engagement with issues of race and empire.

Austen’s novels offer an “inside-outside” perspective on the country house, as she moved in social circles that granted access to such estates without belonging to their aristocratic world. This perspective aligns with Turner’s own position as an artist commissioned by the elite yet observing their world with a critical eye. The exhibition imagines a dialogue between Austen’s literary depictions and Turner’s visual interpretations, exploring how both captured the Regency era’s social dynamics and aesthetic ideals.

I was particularly moved by the many Austen first editions on display: in their display cases, they appeared as immaculate in presentation as they must have done when first published. Preserved so beautifully, it is clear to the viewer that the tomes must have been treasured by generation after generation. It was a great pleasure to meet Professor Jennie Batchelor, Head of English at the University of York and co-curator of Austen and Turner, who talked about the exhibits on show, contextualising them within the life and times of Austen. Professor Batchelor will be giving a talk as part of the lecture series at Harewood in October 2025: ‘Jane Austen, Her Writing and Her Craft’.

A Shared Cultural Lens: The Regency Country House

The Austen and Turner: A Country House Encounter exhibition frames Harewood House as a microcosm of the Regency era, a time of social change, colonial expansion, and artistic innovation. Both Austen and Turner were born into a world shaped by the Industrial Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the expansion of the British Empire. Their works reflect these tensions, with Austen’s novels dissecting the marriage market and class mobility, and Turner’s paintings grappling with nature’s sublime power and human ambition.

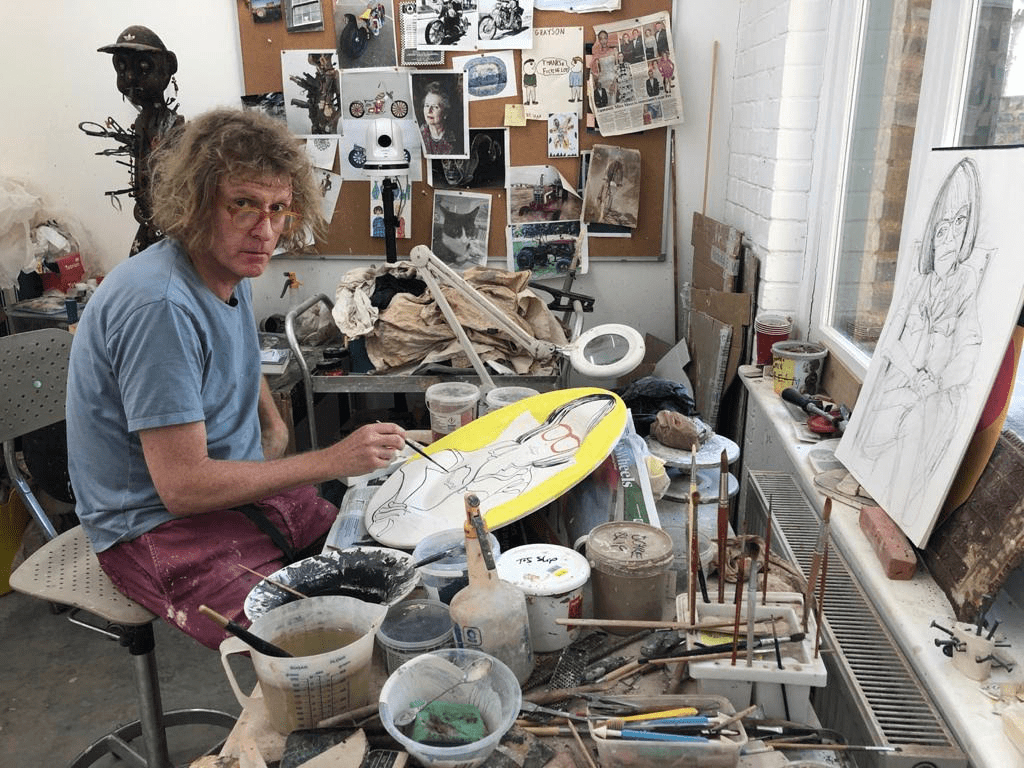

The exhibition juxtaposes Turner’s evocative landscapes with Austen’s manuscripts, letters, and period artifacts like costumes and fashion plates. These objects illuminate the material culture of the country house, from its Chippendale furniture to its Sèvres porcelain, much of which was acquired through colonial wealth. Contemporary interventions, such as new works by visual artist Lela Harris and poet Rommi Smith, Harewood’s Writer in Residence, reframe Austen and Turner’s legacies, addressing the colonial and social complexities of their era.

Austen and Turner’s shared interest in the country house lies in its dual role as a private home and a public symbol. For Austen, estates like Pemberley were stages for personal and moral dramas; for Turner, they were canvases for exploring light, space, and history. The exhibition’s interactive elements, including workshops, Regency balls, and guided walks in “Turner’s footsteps,” invite visitors to engage with these themes, blending historical immersion with modern reflection.

A Personal Connection?

While no meeting between Austen and Turner is documented, a tantalizing personal link exists. Turner’s uncle, Reverend Henry Harpur, oversaw the curacy of Austen’s father, George Austen, in Shipbourne, Kent, early in his career. Additionally, Austen likely knew of Turner’s work, given her interest in art and her social connections. The exhibition playfully imagines their encounter, suggesting a mutual respect for each other’s ability to capture the spirit of their age.

The Austen and Turner: A Country House Encounter exhibition, running from May 2 to October 26, 2025, at Harewood House, is a testament to the enduring relevance of J.M.W. Turner and Jane Austen. Through their respective lenses—Turner’s luminous landscapes and Austen’s incisive prose—they immortalized the British country house as a site of beauty, power, and contradiction. Harewood House, with its rich history and artistic legacy, serves as the perfect stage for this imagined dialogue, inviting visitors to explore the Regency era’s complexities and the genius of two of its greatest observers.

IMAGE TOP: JMW Turner, Interior of a Great House: The Drawing Room, East Cowes Castle, c. 1830, Oil on canvas, 123.9 × 155.0