The opening notes of Chopin’s Étude Op. 25, No. 1 in A-flat major rang out gaily, echoing through the otherwise empty corridor. The young man at the upright piano, so unassumingly accomplished, smiled somewhat impassively. Did we exchange words? We may have done, although I don’t recall, and we would have been led back to our separate wards shortly afterwards. Next to the corridor with its piano was a locked room containing thirty wooden desks and several large plan chests: together, these spaces comprised the arts section of St Anns psychiatric hospital in 2019. For an hour a week, the room would be opened and an untutored art class would take place: for the remaining 168 hours, no staff were available, and so for that time the door remained padlocked.

The underfunding of arts therapy is deplorable, and it is a matter of national shame that it sits within the wider climate of underfunding of mental health services in the UK. “The treatment of severe mental illness in this country has never exactly been good, ” Consultant Clinical Psychologist Dr Jay Watts wrote to ArtReview; “After deinstitutionalization, there was a period where community care was established, but it was too carceral—too focused on medication management and often resulted in long, revolving door admissions.” Economic choices within the UK made this considerably worse, Watts continued: “Since austerity hit, mental health services have been decimated. It’s now routine for seriously mentally ill people to be discharged inappropriately—individuals who would have received long-term care ten years ago—or to experience iatrogenic trauma, harm caused by poor medical care and frequent misdiagnosis. From the late 2000s, efforts to destigmatize mental illness led to a focus on mild mental health problems, causing a denial of disability at the severe end. It’s difficult to overstate how dangerous this has been and continues to be, especially as austerity-driven benefits cuts from 2010 on have left people not only materially impoverished but also psychologically harmed, as many are made to feel they’re failing at simply being human.” When the media, politics and society at large marginalise and demonise mental illness, “art is a rare place—perhaps the only place—where the shattering, shape-shifting, soul-draining shock that often accompanies severe mental illness can be registered somehow”, Dr Watts stated.

The issue is not unique to the UK. Speaking from Brazil, artist Gustavo Nazareno, whose influences include Arthur and João Timóteo da Costa, Estevão Silva, Peter Doig, Tracey Emin, Aaron Douglas and Richard Avedon, and whose show Orixás: Personal Tales of Portraiture runs at Opera Gallery London from 8 October, is firm in his belief that art can help where health services may neglect to do so. “For me, since my childhood art has been a form of escape,” he told Cultural Capital, “my calling as an artist came from a desire to develop my own world.” Nazareno, a self-taught artist, felt his depression lift as he developed his artistic practice, all while moving from the municipality of Três Pontas to São Paulo. That he could develop his artistry was important in a city where quality healthcare is most available to those who can afford it. “The public mental health system in Sao Paulo is challenging and not too different from that of the UK, maybe worse.” Nazareno confided.

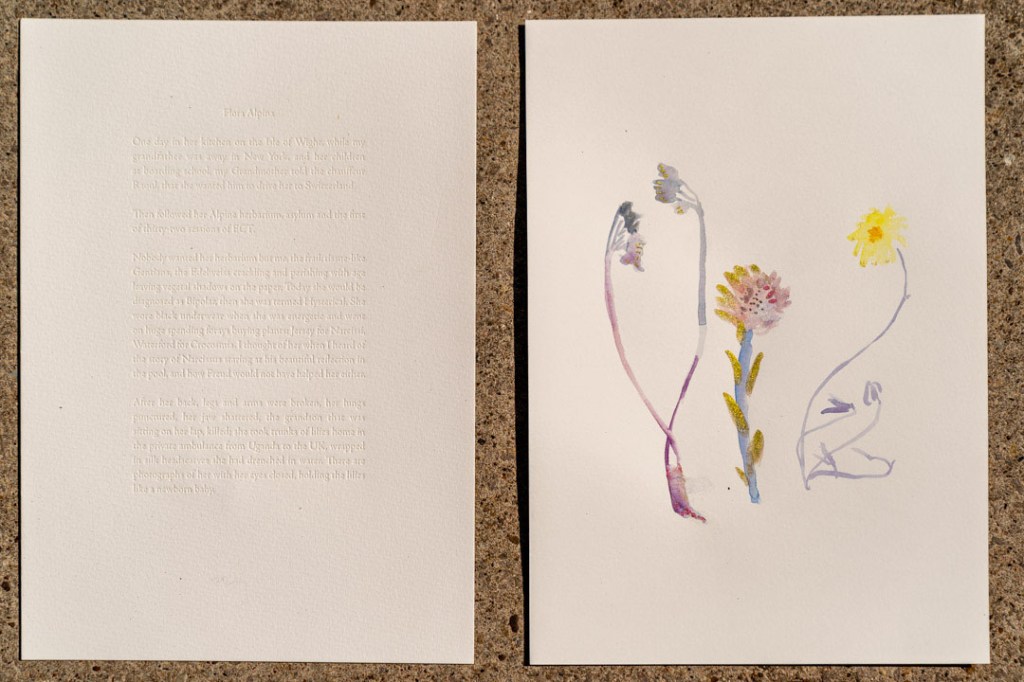

Across the world, in her autobiography Infinity Net, Yayoi Kusama writes of how pressures from her family and community worsened her mental health while in Japan, to the point where she could no longer paint: thankfully, though she was treated by a doctor who was interested in the benefits of art therapy, and was able to create again from the safety of the hospital. Where artworks relate directly to treatment received within hospital settings, both awareness of illness can be raised, and hope for the future can be fostered. A piece of work that is in The Women’s Art Collection, Cambridge, called Flora Alpina, looks at artist Annabel Dover’s grandmother’s mental health and years of ECT and relates it to the trauma of holding her grandson when he was killed in a car accident. Painted with pigment and mica from the plants and rocks of Les Pléiades, its beauty invites contemplation and empathy, in a world where mere mention of ‘mental illness’ can at best sometimes invite apathy through its ubiquitous usage, or else outright discrimination at worst.

It is, of course, hugely reductive to suggest that with adequate mental healthcare and arts therapy provision, service users’ lives would be perfect: work and the benefits system are factors massively affecting well-being on a large scale. “Many people on benefits report that their experience of the system has led to their mental health deteriorating, whether because of having to survive on a woefully inadequate level of income, being put through stressful assessment processes, or facing the prospect of losing their benefits if they cannot comply with strict conditions,” Tom Pollard, Head of Social Policy at the New Economics Foundation wrote to Cultural Capital, “There is a clear and well-established relationship between financial insecurity and poor mental health and for many people the benefits system is failing to provide real security.” What would optimal change look like? “[In an ideal world] everyone should know that they can rely on the solid foundation of never being able to fall below a level of income that allows them to meet their basic needs,” Pollard stated, “The New Economics Foundation’s proposal for a ‘Living Income’ would mean that benefit rates are linked to a meaningful assessment of what people need to meet their essential costs and that people are positively supported towards good jobs (where this is possible) rather than being pushed into any job going.”

One way of marrying service users’ desire for gainful and sustainable employment with a programme that supports their artistic development is exemplified by Bethlem Gallery: a visual arts organisation in south-east London. Established in 1997 at Bethlem Royal Hospital, they support the professional development of the artists they work with. “Bethlem Gallery provides a physical and digital space for the promotion of work made by people who have found visual production enormously beneficial during struggles with mental illness, explained Sue Morgan, gallery artist for over twenty years. “It provides a non-judgemental environment where conversations about art can lead into more general discussions about mental illness and its management. I know many people who have found a new identity as an artist in this space. In my case (I don’t think I am the only one) I can confidently say that I would not have stayed on the planet without the support the gallery has given me.”

The world increasingly needs to incorporate interventions outside of traditional medicine – interventions that are empowering and affordable; real and grounded – in order to address threats to public health. Having spoken to artists and engaged in art workshops, it is my belief that it is art that is the intervention outside of traditional medicine that could be the most powerful. In this universe with its stresses, its traumas and its inhumanities, we must create our own worlds. Let us do so through art.

Gustavo Nazareno: Orixás: Personal Tales of Portraiture ran at Opera Gallery London from 8 October – 9 November 2024. Yayoi Kusama: Every Day I Pray For Love ran at Victoria Miro in London from 25 September – 2 November 2024. IMAGE TOP: Flora Alpina, Annabel Dover

Frances Forbes–Carbines is a writer with pieces in publications including The London Magazine, Antigone Journal and UnHerd.